As part of its commitment to pay $82.6 million to Berkeley in the next 16 years, UC Berkeley will funnel $920,000 into the city’s Housing Trust Fund as recompense for demolishing eight rent-controlled apartments in order to build the 772-bed Anchor House dormitory, according to a settlement between the city and the university.

The university also will “explore relocation and the cost of relocating the eight-unit building at 1921 Walnut St. and if it is technically feasible, to a site to be determined,” according to the agreement. Mayor Jesse Arreguín said today that the city is already looking for land and will soon reach out to private developers with expertise in moving historic properties.

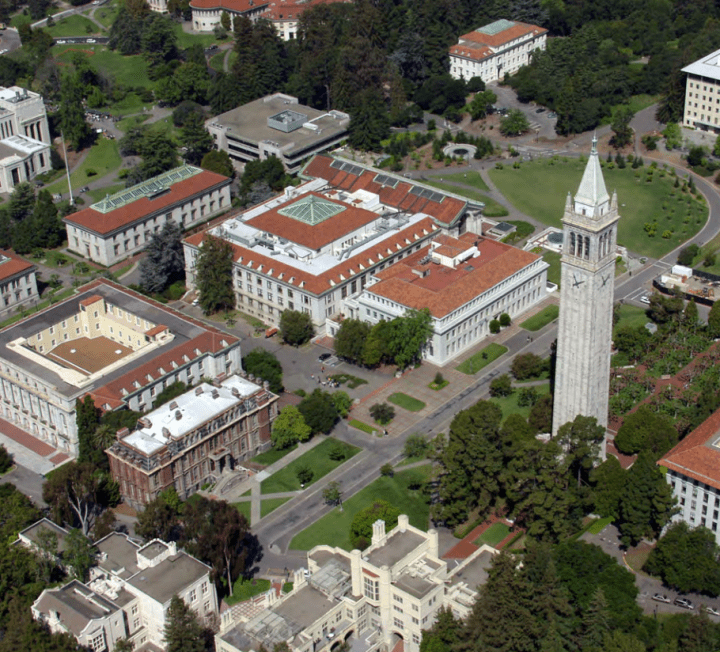

Those are some of the new details that emerged after UC Berkeley and the city of Berkeley signed a new settlement agreement Tuesday that governs how the two entities will interact over the next 16 years. The settlement supersedes the one the two bodies signed in 2005 over Cal’s long-range development plan. This agreement goes from 2021 to 2037, about the length of UC Berkeley’s newest long-range development plan, which the UC Board of Regents approved July 23, along with an accompanying environmental impact report.

Berkeley and Cal had released some, but not all, of the details on July 14 after the Berkeley City Council voted 8-1 in a closed session on the overall concept. City Councilmember Kate Harrison voted against the agreement.

UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ told the Regents last week that the $82.6 million payment was a “historic campus investment.”

“Enormous step forward for the city and the university”

On a broader level, the settlement sets out a framework and codifies a commitment between Berkeley and Cal to work more closely on zoning, housing, enrollment growth and other issues. The two sides will meet annually to review the implementation of the agreement and Cal will provide written reports on its 2021 LRDP, enrollment changes, and housing production. UC Berkeley also has agreed to notify the city, and seek formal input, on capital projects off-campus costing more than $5 million and to consider the city’s critiques. Berkeley has agreed to withdraw from two lawsuits challenging UC Berkeley’s growth and development. It will not sue over UC Berkeley’s 2021 LRDP or EIR, either. It will not fight plans to build the Anchor House project or a student housing complex on People’s Park either.

One example of this new attitude of reconciliation will happen at the project planned for Upper Hearst, where university-hired architects have designed a modern housing complex on Hearst and La Loma avenues that critics think doesn’t fit in with the historic neighborhood. UC Berkeley has agreed to “consider any comments and concerns regarding … proposed final design and color scheme,” according to the settlement.

“I think this is an enormous step forward for the city and the university and will set the tone for a new relationship,” said Arreguín. UC Berkeley “has enormous power. It is exempt from local laws and regulations. The only leverage we have is a good relationship or legal power. I think we’ve leveraged both.”

Some details in the settlement:

- UC Berkeley will pay Berkeley $4.1 million annually, adjusted 3% a year for inflation. That adds up to about $82.6 million over the life of the settlement. UC Berkeley had been paying the city $1.8 million annually under the 2005 agreement. Some of the spending specifics for the next two years were detailed in the document.

- $2.8 million of that will go annually to pay for fire and other city services.

- At least 30% of the annual payment, about $1.3 million, will be used to benefit Berkeley residents living within a half-mile of the university. This could include paying for police patrols, new street lights, vegetation management, and improving bike and pedestrian pathways, among other ideas, said Arreguín.

- In 2021, $130,000 of the $4.1 million payment will go toward building a public restroom in the Telegraph Avenue area.

- In 2021, some of the proceeds will go toward funding a daytime drop-in service center in the Telegraph Avenue area for those who are unhoused.

- In 2022, $250,000 will be allocated to the Piedmont/Channing area for traffic circle pedestrian and street lighting improvements.

- Funds will be allocated in 2022 to wildfire risk management and fuel reduction on UC Berkeley property.

- UC Berkeley will donate land off the main campus for the construction of a new city fire station, most likely on the Clark Kerr campus or the Fernald-Smyth property, said Arreguín.

- UC Berkeley will continue to fund the position of a campus social worker to work with the unhoused population as long as there is a demonstrated need.

- UC Berkeley will endeavor to continue its $300,000 annual Chancellor grants to joint projects.

- UC Berkeley “will cooperate in good faith” with Berkeley to collect certain parking taxes from university-owned lots.

- Cal will require its commercial tenants operating in the city environs to get Berkeley permits and pay city impact fees.

- UC Berkeley will collaborate in good faith to reach an agreement to “reduce or eliminate its use of master leasing of residential facilities.”

- Berkeley, in the interests of increasing student housing opportunities, will evaluate zoning adjustments to do this, including allowing 12-story buildings in south Berkeley directly south of the campus. A planning process for this is underway, said Arreguín.

- The parties recognize the importance of keeping properties on Berkeley’s tax roll, and Cal commits to trying to put new programs and parking facilities on UC Berkeley-owned land.

- If undergraduate growth exceeds 1% per year for three consecutive years, the two sides will meet to discuss the potential physical impacts of the increases and discuss potential changes to the agreement. In 2019, Berkeley sued the university for adding in a 33.7% growth in student enrollment to a supplemental EIR for the Upper Hearst project. Arreguín said Cal had not been forthcoming in the past about its enrollment increases and he even had to file a public records act request to find out enrollment numbers. This new action should reduce surprises, he said.

- UC Berkeley agreed to lease land in People’s Park to Resources for Community Development or another group to build affordable and permanent supportive housing for the homeless. UC Berkeley has verbally done this but now this is more enforceable, said Arreguín.

Harrison, the lone ‘”no” vote on the council, said she likes aspects of the settlement, particularly UC Berkeley’s higher annual payments, but found fundamental parts of it lacking. There is one lump sum for police, fire and other city services, for example. Harrison would like to have seen some flexibility on the fire payments as fire seasons are getting worse and costs could go up, she said. In addition, she doesn’t understand why Berkeley will take part of the $4.1 million annual payment from the university and use a portion of it to clear vegetation on the UC campus.

The timing was bad, too, as Berkeley had just won a court victory where an Alameda County Superior Court judge ruled that UC Berkeley would have to do an environmental analysis of its 33.7% student enrollment growth in recent years. Harrison wanted to know more about that impact, she said.

Harrison said she was also opposed to UC Berkeley’s plans in its LRDP to add about 3,000 additional parking spaces at a time when the city is reducing parking. By agreeing not to sue over the LRDP, Berkeley lost its chance to push back against that, she said.

Most importantly, Harrison wanted some sort of tie between student enrollment and housing construction, much like three other campuses, UC Davis, UC Santa Barbara, and UC Santa Cruz, have agreed to, she said.

“We don’t require building before enrollment,” she said. “I feel that is the wrong way again.”

City Councilmember Sophie Hahn said she thinks the agreement was the best the city could do given the unequal power dynamic with UC, a state institution that does not have to comply with local laws.

“My job is to do the best I can do for Berkeley,” said Hahn. “That does not always mean getting everything I would like to see. … What I would like is for the Regents to consider the impact all the UC campuses have on their host communities and create some standards for ensuring those communities are compensated for the impact from the non-tax-paying entities.”

Harvey Smith, part of a group fighting the development of People’s Park, said his reaction, and that of others, is that because of the recent court ruling, Berkeley “snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. The city was in a good bargaining position,” he said. Smith is a member of a group that has filed a lawsuit against Berkeley, stating that the city violated the Brown Act, which governs meetings, by voting in a closed session about the settlement but not immediately announcing the vote. Berkeley City Attorney Farimah Brown said that the vote was provisionary since the Regents had not voted yet and it did not have to be announced.

Advantages of a cooperative relationship

The settlement agreement details the advantages of having a cooperative relationship between Berkeley and UC Berkeley and acknowledges the symbiosis of the entities:

“The City recognizes the significant contributions that the University makes to the surrounding community and supports its efforts to plan for future needs,” reads one part of the statement of “shared goals and principles.”

“The University recognizes that the City environs are as much a part of the University experience as the campus itself, and the quality of City life is a large part of what makes the University a unique and desirable plan to learn, work and live,” reads the next line.

The agreement discusses how Berkeley and Cal will interact over zoning and housing issues going forward. They will work together to establish a “collaborative planning process for the City to review and comment upon campus capital projects located in the City environs.” UC Berkeley will continue its practice of “typically voluntarily honoring the City’s existing zoning standards.” Cal will consult with Berkeley planning staff, politicians, and community members about off-campus projects and respond to “reasonably identified concerns.”

Development of Clark Kerr campus

Berkeley agreed to withdraw its support of a lawsuit filed by Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods against the construction of new volleyball courts at the Clark Kerr campus. Berkeley had joined the suit because the university had not followed the rules for developing the satellite campus laid out in a 1982 memorandum of understanding, said Arreguín. Cal went forward with development plans even though the MOU required any changes to the campus to be approved by the Berkeley City Council, he said.

UC Berkeley countersued four neighborhood leaders who own property around the campus to challenge the covenants put in place in 1982 to protect approximately 700 property owners on all sides of the Clark Kerr Campus. The covenants were a condition of the transfer from the State of California and the judge recently ruled that UC had to sue all property owners who are benefitted by the covenants.

Cal is bound by the MOU until 2032 but has indicated it intends to build more housing at Clark Kerr. The new settlement agreement states “the city wished to work cooperatively with the University in planning for future capital projects on the Clark Kerr campus … and advance projects that will improve the (adjacent) neighborhoods.” The agreement states that UC Berkeley will consult and work cooperatively regarding potential expanded public access to recreational facilities on the Clark Kerr campus.” It also states that the city will actively engage neighbors and the community in providing input for future development plans.

If UC Berkeley prevails in its attempts to dissolve its agreement with the 700 property owners, it will still be obligated to Berkeley, said Harrison.

What will happen to 1921 Walnut St.?

A remaining question mark is the future of 1921 Walnut St., a 112-year-old rent-controlled building now in the path of the Anchor House project. Construction on that 772-bed dorm for transfer students is scheduled to start in November. The settlement discusses moving the building, which is technically possible, said Arreguín. However, moving it would only be done as long as it “does not result in increased time to the Anchor House Student Housing Project or delay the construction,” of the project.

Arreguín said both sides were looking to find a “creative solution,” to keeping the building instead of relocating the six or so tenants remaining. “We are earnestly trying to make it work,” he said.

UC Berkeley has not committed to moving the building yet because there are so many unknowns, said Kyle Gibson, the communications director for Capital Strategies for UC Berkeley. The settlement is a commitment to see if the building can be moved, he said. It may be technically possible to move the structure, but not feasible as there are challenges in the way the apartment complex was built.

Natalie Logusch, one of those tenants, and one who is fighting relocation, said her group has still not heard directly from UC Berkeley and feels the city needs to do a better job communicating. The way the section of the settlement agreement is worded raises “a lot of questions? “What will this process be like?” she said. “It doesn’t specify whose obligation it is to do what. Will UC and the city do it together?”

“My immediate reaction and fear is both parties can wiggle out of this,” said Logusch.

Editor’s note: The headline was changed after publication to show that UC Berkeley is exploring moving the building but has not committed to moving the building.