The predictions that AI will kill millions of fabrication jobs are sobering. But George Chittenden, co-founder of a West Berkeley manufacturing company, is not worried that his business will have to fend off a robot takeover. The company does scientific glassblowing, building on a practice that goes back centuries.

“We were fortunate to have picked a field that’s really difficult to automate,” Chittenden said.

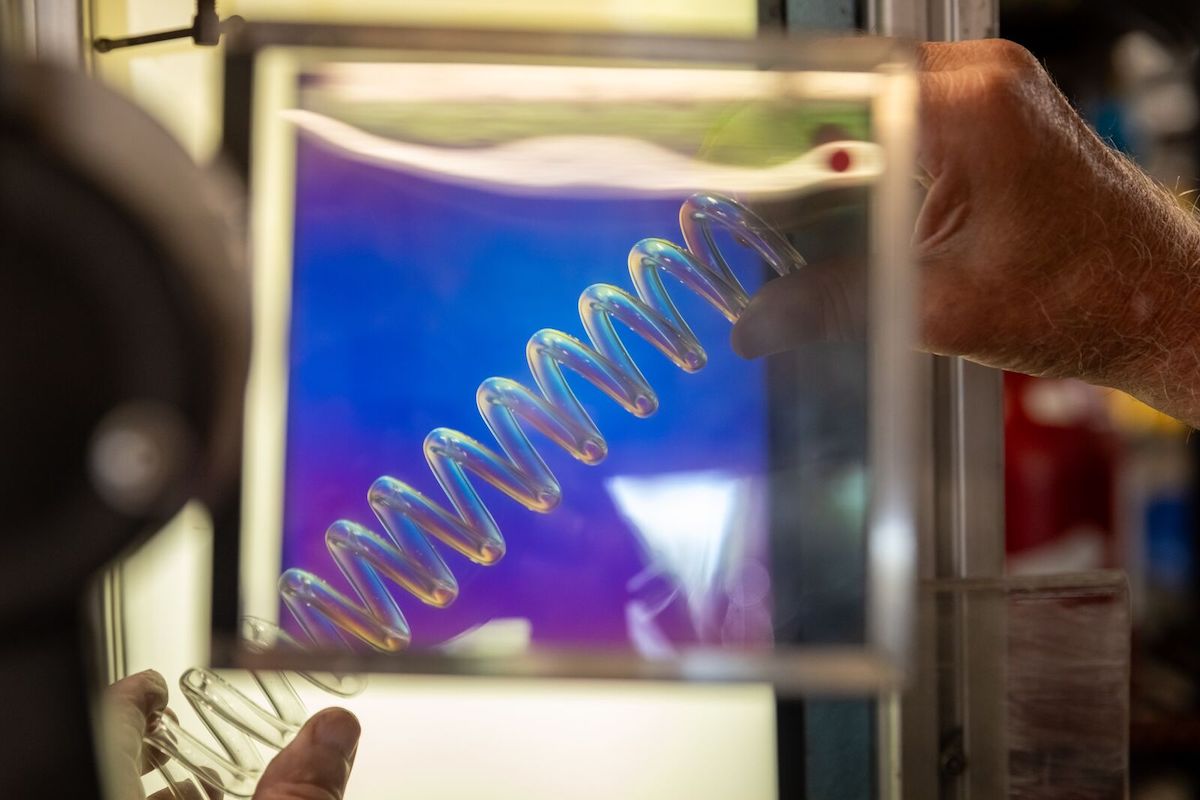

He, alongside partner Tom Adams, founded Adams & Chittenden Scientific Glass 30 years ago. The company makes laboratory glassware and glass tools for an array of scientific and industrial uses. Indeed, its website is a dizzying aggregation of applications: vapor cells and bubblers for laboratories, flange adapters and cold fingers for evaporation projects, manifolds and reactors for peptide syntheses. Everything is made by hand.

Unlike other commonly machined materials, such as metal, plastic or wood, scientific glassblowing is not done “subtractively” — in other words, by removing material. It is a process that is “redistributive,” which inhibits robotic capabilities in all but the most mundane applications.

“The material has to be moved around with heat,” Chittenden said. “You have to take into account how hot it is and how it’s moving. Humans are good at this (with training of course), but it’s complicated for a robot.

“Machines can make bottles and jars” he continued. “But humans are much, much better at processing the large amount of feedback and decision making required for scientific glassblowing.”

Even 3-D printers, which have been celebrated for fabricating such complex structures as hip implants and microturbine components, would fail at the most basic scientific glassblowing challenges. This scenario is compounded by the fact that, often, the company is designing one-of-a-kind glassware based on its knowledge and experience of what the glass is capable of, and what it is not.

On National Manufacturing Day (Fri., Oct. 6) the public will have a chance to see scientific glassblowing in action at an open house hosted at Adams & Chittenden’s West Berkeley shop at 2741 Eighth St. The tour of the business will include live glassblowing demonstrations.

Berkeley Manufacturing Week public tours, Oct. 2-6. Businesses include Boichik Bagels, Takara Sake, Artworks Foundry, Berkeley Potters Guild, Zenbooth, Metro Lighting, and TCHO Chocolate. Organized by the City of Berkeley’s Office of Economic Development. Trumer Brewery will celebrate its new Taproom Grand Opening and Oktoberfest Oct. 7.

But, Chittenden notes, visitors to Adams & Chittenden should not expect to see workers in smocks blowing glass through long pipes in front of blazing furnaces. “It will actually be more like a machine shop,” he said.

For starters, scientific glassblowing is done with “localized” heating using welding torches, not pipes, and uses gasses such as hydrogen and oxygen, not furnaces, as fuel. And while blowing is certainly one of the techniques, “so is sucking, spinning, slumping, etc.” To find out what those are, people will just have to attend the open house.

Adams and Chittenden came to scientific glassblowing from different paths. Adams graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in physics and went to work at R&D Glass, which was one of several such shops doing work for the university.

Chittenden, by contrast, started out studying science but drifted into art, which led him to glassblowing as an art, and then back to glassblowing as a science. “It’s funny,” he said. “I’ve been fortunate to have stumbled into a field that combined my interests in a remarkable way. I lucked out.”

They became friends when they crossed paths at Balkan dancing. “Balkan dance in the Bay Area proved to be a powerful community. Berkeley’s own Ashkenaz was an important community center for dancing, whose founder David Nadel was himself a Balkan dancer. We’re talking about connections that were made more than 50 years ago.”

The two founded Adams & Chittenden in 1993. Since then they have built a reputation for making high-quality custom scientific glassware. Their roster of clients ranges from neighbors up the street like UC Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, to international research institutions and biotech companies needing specialized glassware.

“Having the association with the name ‘Berkeley’ no doubt had a good impact on our business starting up. And staying in Berkeley has been great.”

Going co-op

But their long history also prompted a forward-looking reckoning several years ago, including how to transition the business after the two retire. (Adams retired last year, though he still consults for the business.) To that end, in 2019, they converted the business into a worker cooperative, with the assistance of Project Equity. Project Equity helps Berkeley’s Office of Economic Development promote employee ownership transitions (including worker co-ops, ESOPs and Employee Ownership Trusts) for business owners considering succession planning. For Adams and Chittenden, it was a reflection of their values and “the right thing to do.”

“We felt that a co-op was the best way to keep the business vital,” Chittenden said. “We’d both seen what happens when an “outside person” buys a business; doesn’t understand the nature of the work; and the business suffers.

“We did not want a repeat of that scenario,” he continued. “And who better to keep the business alive than the people who work here?” And where better to keep a business going than in the city they’ve been a part of for 30 years?

WHAT NEXT

- Join a Berkeley Manufacturing Week tour (Oct. 2-7) or visit a local producer anytime using the Made in Berkeley map as a guide.

- Attend “Berkeley Today & Tomorrow” (Oct. 11), to celebrate local makers and the innovation, creativity and resilience of Berkeley businesses.

- Visit Discovered in Berkeley to find more stories about exceptional local businesses.