For Janice Myles and her seven siblings, their lives are forever bound up in the life — and death — of their father’s church.

The Rev. Leonard L. Hester and his wife, Parthena, founded New Light Baptist Church in 1954, and right from the outset, it was a family endeavor. Myles and her two sisters grew up singing in the choir, conducted by their eldest brother and accompanied by their younger brother on drums.

In 1977, when Hester moved New Light from Oakland to a former Swedish church in South Berkeley, Myles remembers pitching in to redecorate. The Hesters hung chandeliers and trimmed the sanctuary in gold leaf paint. It all cost her father a fortune, but it was worth it, she said. “It was his sanctuary to God.”

Today, though, the gold leaf paint and chandeliers are long gone, and the building has a radically different decor. Its salmon exterior now slate gray, the property has a wrought-iron spiral staircase, a domed movie screen where the altar once was, and a rooftop jacuzzi with panoramic views of Berkeley and the Bay.

After decades of dwindling membership and donations, the Hesters lost New Light to foreclosure in 2014. Two years later, architect Josiah Maddock bought the historic Black church and spent six years converting it into a six-bedroom, multi-story residence. Maddock currently rents it out to five tenants — a collective of artists and tech workers, none of whom are Black, who say they’re creating a “congregation” of their own.

Since its construction in 1907, the church at the corner of Parker Street and Martin Luther King, Jr. Way has meant many things to many people, from a gathering place for Scandinavian immigrants to the backdrop of a classic MC Hammer music video.

Now, the former church has become a complex symbol — of the Bay Area’s decline in religious practice; of South Berkeley’s shrinking Black population; of debates over gentrification, the legacy of exclusionary zoning and how to solve the housing crisis; and of the neighborhood’s past and future.

A time of growth and thriving

Leonard and Parthena Hester saw moving to South Berkeley as a logical next step, in New Light’s trajectory and their own.

The son of a Methodist minister in Texas, Hester and his family relocated to Oakland in the 1950s; he accepted a music director position at his brother-in-law’s church. Then, in 1954, Hester ventured out on his own, starting New Light Baptist Church at 1451 16th St. in West Oakland and moving to a larger building on 54th Street two years later.

Hester quickly established his church as a musical powerhouse. New Light’s Sunday evening services were broadcast live on KDIA, the Bay Area’s go-to soul music radio station throughout the 1960s and ’70s. Hester’s eldest son, Larry, directed music from 1963 to 1986, but before that, it was conducted by a young Helen Stephens, who would go on to form the award-winning choral group “The Voices of Christ” and work with the biggest names in gospel music. Some of those stars even performed at New Light, like Oakland-born gospel pioneer Edwin Hawkins, best known for his chart-topper, “Oh Happy Day.”

New Light also built a reputation for the miraculous. In 1972, 10-year-old Cloretta Starks reportedly exhibited the signs of stigmata — bleeding from her palms, feet and side, each of the places where Christ was wounded. Larry Hester said he witnessed it: “My mother wiped the blood with her handkerchief.”

The phenomena drew widespread media coverage as well as numerous miracle-seekers. Over the next five years, Starks claimed to have experienced the stigmata three more times, and Rev. Hester helped organize a week of healing services around the girl called the “Youth Supernatural End-Time Revival.” “Bring the sick, troubled, the dope addict and the possessed, and depressed,” one newspaper ad exhorted.

In 1977, Hester moved his growing congregation to a church at 1841 Parker St. The building had already lived two full lives since its construction in 1907 for a longtime sailor’s missionary and his congregation.

First called “Svenska Missionen,” or Swedish Mission Church, and later renamed Berkeley Covenant Church, it remained a hub for Scandinavian immigrants and their descendants, offering Sunday services in the “mother tongue” well into the 1920s.

Then, in 1954, Berkeley Covenant moved to a larger building on Hopkins Street. In a ceremony that year, church leaders handed off the keys to Grove Street Christian Church — a predominantly Black congregation that thrived until 1977.

Like so many churches of the era, Grove Street regularly served as a civil rights gathering place. Along with other Berkeley churches, the church helped host the Black Odyssey Festival, a series of lectures and cultural activities created to honor Martin Luther King, Jr. after his death and sponsored by the Graduate Theological Union. And throughout the 1970s, the Berkeley chapter of the Gray Panthers — a multigenerational advocacy group established to combat ageism and fight for other social justice issues — consistently met at 1837 Parker St., the pastor’s residence next door to the church.

Eventually, Grove Street sold its property to Hester, but only because its 200 members successfully merged with a shrinking white congregation in East Oakland.

The Parker Street church’s transition from a Scandinavian church to a largely Black one tracks with South Berkeley’s evolution in the middle of the 20th century. “It was this time of growth, specifically of Black people,” explains Brandi T. Summers, an associate professor of Geography at UC Berkeley. “Many of them were now able to move to parts of Berkeley and create their kind of community.”

Before and during the Second World War, thousands of Black Americans arrived in the Bay Area as part of the Great Migration, fleeing the strictures of the Jim Crow South and seeking the promise of industrial jobs. In the 1940s, Berkeley’s Black population nearly quadrupled — even as housing discrimination largely confined them to neighborhoods south of Dwight Way and west of Grove Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Way). At the same time, white residents exited the flats in droves, often relocating to more spacious suburbs like Orinda and Moraga, Summers said. South Berkeley lost roughly a third of its white residents between 1940 and 1950.

When New Light took up residence on Parker Street, the neighborhood was 80% Black. Still, even with all the demographic changes, Larry Hester doesn’t recall too many Black Baptist churches in the area back then, at least with music like New Light. “We definitely brought, I like to say, a little soul to Berkeley,” he said.

Hester had the church repainted, inside and out, and flung the doors open wide every Sunday “so the music could go out to the community,” Myles said.

She remembers New Light as interracial and interdenominational, drawing in hundreds of neighbors, Cal students and Sunday commuters. “We had members that drove from Tracy and Stockton just to come to service.”

A struggle to stay open in a changing neighborhood

In 1985, Leonard Hester died at age 64 after a sudden illness. At his memorial service, Myles was overwhelmed by the turnout. “We literally had to block the street off and put chairs outside … he was a pillar of that community.”

Hester’s death sent shockwaves through the family and, by extension, the ministry. Larry Hester, grieving the loss of his father “and his particular way of church,” left New Light entirely, while Myles soon moved to Arizona with her husband and family. Michael Hester, the second youngest son, took over for his father, with his older brother Ernest at his side. (Michael and Ernest Hester did not respond to requests for an interview for this story.)

Michael Hester took New Light in some bold new directions. “He wanted to extend his ministry beyond the traditional boundaries of the local church,” observed Rev. Robert McKnight of The Rock of Truth Church. He drew in a younger crowd and even briefly moved the church to the Laurel Theater — a since demolished art deco movie palace on MacArthur Boulevard — leasing out the Parker Street property to McKnight’s church. But the changes did not sit well with some longtime members, and many left. Within a few years, Michael Hester and New Light returned to the smaller sanctuary on Parker Street.

The church body fluctuated over the coming decades. Still, New Light remained an epicenter of gospel music for years. Michael Hester’s cousin, James L. Richard II, recalled regularly seeing international students among the usual crowd; apparently, an instructor at UC Berkeley Extension recommended the church as “a taste of Black culture.”

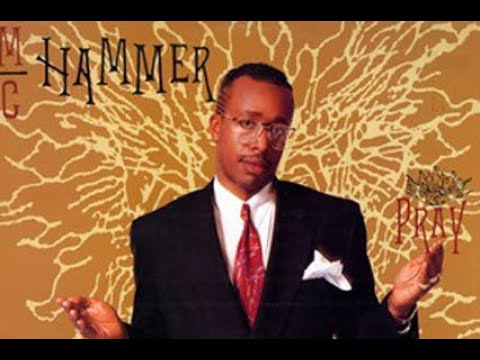

In 1990, the church got an unexpected dose of publicity: Oakland native MC Hammer chose New Light as one of the settings for “Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ‘Em: The Movie,” the direct-to-video companion for his multi-platinum album of the same name. The video shows rap’s first megastar strutting behind the pulpit and rapping his hit “Pray,” flanked by record-spinning deacons and backed by a hip-hop choir.

By the 2000s, though, New Light (its name changed to New Light Christian Center) struggled. Alameda County put multiple liens on the church, which Michael Hester later resolved. But then, in 2008, Ernest Hester started his own church, Tremendous Faith Christian Center. He took many New Light members with him, gathering at an Adventist church only a few blocks down Parker Street.

Simmering beneath all of this, of course, was a rapidly transforming Berkeley. The greater Bay Area was on its way to becoming the least church-going metropolitan area in the country. In conjunction, South Berkeley’s Black population, around 80% in 1980, dropped to 30% by 2010.

This was largely displacement — the result of gentrification, soaring rents and home prices, the racial wealth gap, the 2008 financial crash and the region’s failure to build enough housing. But in some cases, it was also a sign of success, Summers emphasized. Many middle-class Black families could now move elsewhere, she said, buying larger homes with yards and walkable neighborhoods, achieving “what they’d been desiring for so long.”

Michael Hester endeavored to keep New Light alive despite a reconfiguring neighborhood and declining attendance. Finally, though, in 2014, the bank foreclosed his church. For the first time in nearly half a century, the Parker Street church was out of the Hesters’ hands.

A new use for an old church

When architect Josiah Maddock bought the church for $539,000 in March 2016, “it was the only building in Berkeley I could afford,” he said. He already had a few major projects under his belt, including a luxury high-rise in Honolulu and another tower in San Francisco. But at 36, a few years into running his own architecture firm, he was looking for something unique — a project he, his partner and his dog could live in while they rebuilt it.

Then he visited the church and was immediately smitten: “I could tell as soon as I walked into the building how special it was.”

Maddock said his primary concern was what the community would think. “The last thing I wanted to do was be a disrespectful, non-present developer that just chopped the building up into a bunch of pieces and maximized the profit.” He made a point of going around to his neighbors — some of whom had attended New Light — and letting them know his plan to rehabilitate and repair the space.

Maddock and his partner spent six years converting the church. They repaired the walls and roof, removed the pews and installed a kitchen island, and built offices in the steeples. Throughout the process, there was very little community outcry, Maddock said. On Facebook, however, some former parishioners grieved.

“I’m feeling some kinda way about this gentrification,” one member posted in October 2019, sharing a photo of the refurbished property, now adorned with Halloween decorations. Reactions were strong. “God is not pleased period,” one commenter wrote. “Sad,” another replied. “We have to fight to keep our history.”

But there was never any concerted pushback — perhaps, McKnight believes, because those who cared were gone. “Long-time members of that community had passed away or moved on. And the next generation, they went away to school, they found jobs, they were able to purchase homes, and many never returned.”

In late 2022, Maddock and his partner moved to Los Angeles and handed the property off to renters for the first time, marketing it at over $10,000 per month. They were choosy about who would take over the building, looking for tenants who “understood the space” and would care for it, Maddock said. Eventually, they found their match: a collective of artists and tech workers who had come together in San Francisco.

The building was formally converted to a single-family home, which the five tenants see as fitting. “We are a single family,” said one resident, an aerial acrobat who daylights as a technical writer for Google. After trying out another living situation, she said, the group felt this space could truly be a “canvas for community building.”

They’re still experimenting to find what that looks like in practice. In the last year, they’ve housed artists-in-residence for free or cheap and hope to provide performance space for up-and-coming bands and playwrights. First and foremost, though, the group views the space as a home. Another resident, a musician and software engineer, sees poignancy in the fact that they live in a former place of worship. “We’re trying to build something here that is long-lasting and intentional,” he said.

“None of us are Black in this place that was predominantly Black,” he recognized.

They’re still new to the area, he noted, and getting to know their neighbors. But they feel a “reasonably high degree of responsibility” to “provide a space that helps the people around us, helps the community grow, and helps folks feel supported.”

As for how to honor the property’s heritage, the tenants are still finding their way. During a tour of their home, as we were about to scale the spiral staircase on our way to view the rooftop jacuzzi, a resident gestured downward. The floorboards — left unchanged in Maddock’s remodel — were discolored in conspicuous rows, revealing where pews once were. The resident eagerly pointed out numerous shoe-sized scuffs where congregants’ feet had worn grooves in the floor. “It’s cool to see,” he said, “thinking about the history and all that.”

‘It’s not about the building’

Larry Hester still lives in Berkeley and frequently drives past his father’s former church. It pains him, he said. “My Camelot hope was always that it would be the monument of my dad’s life.” Instead, he’s had to face a very different reality.

As religious demographics reconfigure, experts say that more and more churches will inevitably shutter, in the Bay Area and beyond. With death comes new possibilities, although what those are depends on who you ask. In San Francisco, century-old churches like New Light have been resurrected as roller rinks, art galleries, and other community spaces.

Maddock, for his part, believes former churches can be used to address Berkeley’s housing crisis, albeit imperfectly. “Every unit of housing is a good thing in the Bay Area,” he said. He hopes to build “a bunch more co-living spaces” like 1841 Parker St. in the future.

Housing advocate Darrell Owens, who grew up not far from New Light, generally agrees, although he contends that single-family residences like Maddock’s are “insufficient to meet Berkeley’s needs.” After decades of producing little housing, Berkeley is now exceeding state housing goals but still falling significantly short of targets for low-income homes. Ideally, Owens would like to see former church plots converted into subsidized housing.

That’s the kind of project other Berkeley churches are already pursuing. In May 2022, North Berkeley’s first affordable housing complex in three decades opened on land belonging to All Souls Episcopal Parish. The century-old McGee Avenue Baptist Church recently partnered with Bay Area Community Land Trust to transform a dilapidated church building on Stuart Street into an affordable eight-unit co-op. And St. Paul AME Church on Ashby Avenue plans to develop its old offices into a 52-unit apartment complex, with 10 units reserved for formerly homeless individuals.

Given the city’s dire need for affordable housing, the project was “obvious,” said Pastor Anthony Hughes of St. Paul AME. He recognizes that Berkeley should have a range of housing options, including single-family homes. Still, Hughes said, quoting Matthew 25, “I’d hope that anybody who is repurposing a property would build something to help ‘the least of these’ among us.”

A new California law aims to stem the housing shortage by encouraging projects like these. SB4, which went into effect Jan. 1, allows faith-based organizations to more easily convert parking lots and unused land into affordable housing. The law frees up some 171,000 acres throughout the state — nearly five times the size of Oakland — according to recent research by Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley.

It’s possible that legislation like this, if passed earlier, could have kept New Light alive; in addition to the church, the Hesters owned the four-bedroom pastor’s residence next door, which was sold in 2015. For struggling churches today, the chance to transform excess land into affordable housing could be a “lifeline” in helping “churches leverage their land and avoid foreclosures,” said David Garcia, policy director at the Terner Center.

Owens said he was shocked but not really that surprised to learn of New Light’s fate. “An old Black church becoming a mansion is perfectly in line with all the other changes in South Berkeley,” he said.

Still, he noted, the onus is not on Maddock for building a home; it’s on the city. Berkeley zoning laws only allow for one unit per 1,650 square feet at the site. With a small lot under 3,000 square feet, a single unit was the most Maddock could build. “A measly single-family home doesn’t do anything,” Owens said. “But Berkeley zoning more or less asks for it.”

City leaders launched a process to end single-family zoning in 2021, though it may be years more before actual zoning changes are made in South Berkeley.

For Summers, the Cal geographer, the Parker Street property and its tenants encapsulate Berkeley’s gentrification to a “dystopian” degree. “The artists are attempting to beautify and create community as if community doesn’t already exist,” she said.

While she is all for affordable housing, Summers believes former churches like New Light should remain spaces that serve the broader community, like parks and food co-ops. Addressing gentrification requires more than building apartments, she argues. “We need to think more holistically as it relates to life, not just a place to sleep, or cook dinner, or park your car.”

Like her brother, Janice Myles wishes New Light could have lived on, or at least remained a church. At the same time, she’s convinced her parents’ legacy extends far beyond Parker Street, carried on in the lives of present-day pastors like her brother Ernest.

“Buildings fade away,” she said. Still, there’d been so much singing over the decades, she joked, that she wondered if the tenants ever hear voices emanating from the drywall. “I’m sure they’re there. I’m positive they’re still coming out of those walls.”

“It’s not about the building,” Myles added. “It’s about the people.”

Note: The name of a tenant interviewed by Berkeleyside has been removed from this story due to an editorial communication.

Hayden Royster is a playwright and journalist from Oakland who writes at the intersection of belief and culture. Find him on X (for now) at @haydenroyster and haydenroyster.com.